[Guest blog post by Scott Edwards and Christoph Koettl from Amnesty International USA]

Just a few short weeks ago, Amnesty International celebrated its 50th anniversary. Over the course of 50 years, Amnesty International as a brand and a non-governmental organization has become an important actor in the international space—not only as a global grassroots movement agitating for the universal respect of human rights, but as a supplier of credible and accurate information on human rights abuses.

Perpetrators of human rights abuses have little recourse when confronted with Amnesty’s reporting of human rights failings. While other actors in the international sphere may be faulted for having mixed motives, or politically expedient reporting, the rigor of documentation in Amnesty reporting—like many other, younger human rights NGOs—defies the standard methods of denial and minimization perpetrators may pursue. This authority and credibility is strongly protected. Amnesty researchers are always on guard for how perpetrators might attempt to undermine or question research, and as such, take great steps to ensure rigorous verification of their research findings and evidence. The fall-out from botched research might be quite dramatic—see the recent “Gay Girl In Damascus” fiasco—not the least for future victims who will definitely not profit from a damaged reputation of human rights watch dogs.

Bridging Divides and the Empowerment of New Agents

Over the past few years, there has been a dramatic increase in the numbers of people with access to digital communications—including internet access and mobile phone service—especially in the Global South. This trend has empowered more people to connect with others, and further to become voracious consumers of information. Importantly for human rights watchdogs and advocates, however, relatively new users of digital tools are using them to communicate their experiences outwardly. Across the globe—and without any organizing or mobilization by NGOs or watchdogs—people confronted with threats to their rights are communicating out those experiences, in effect reasserting agency over their own rights protection. Faced with a deluge of such self-reporting made possible through social networking tools, and platforms such as crowdmap, Amnesty and other grassroots human rights organizations must address the question as to how to integrate these self-reported experiences and testimonies into their traditional methods of research and analysis, especially given the importance of reporting credibility in the ability of advocates to effect policy change.

[caption id="attachment_4437" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Amnesty International’s use of crowd sourcing in a campaigning project on Kenya, in which nearly 50,000 people participated"] [/caption]

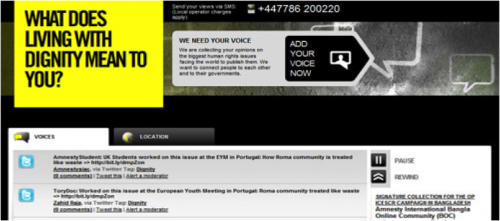

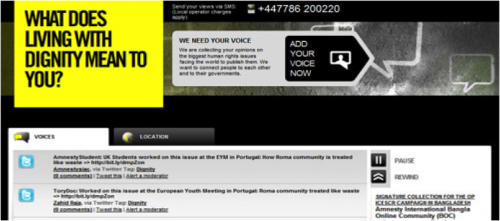

While AI has played a leadership role in the use of new technologies for human rights monitoring—such as the use of geospatial technologies such as satellite imagery, crowd sourcing does not yet count as a standard methodology or data source in the work of human rights watchdogs. However, that might slowly change. Amnesty previously used crowd sourcing the context of activism and mobilization. For example, as part of the launch of its new flagship campaign to fight poverty, the organization created a platform to amplify the voices from Kenyans, who were describing their understanding of “Dignity”.

Saudi Arabia Crowdmap

The Arab Spring, with its massive popular uprisings and use of social media tools to organize, provides further urgency to test and expand the use of crowd sourcing, including gathering human rights related events information. Of all the countries in the Middle East and North Africa Amnesty chose Saudi Arabia to deploy its first crowdmap--a strategic—yet challenging—choice. The country has not received a lot of attention in the wake of the Arab Spring, and remains extremely closed and restricted, with little information outflow. We know, however, human rights violations are widespread and widely underreported. This is largely related to a prevailing culture of secrecy, no matter if in regards to the justice system or the specific conditions of (political) prisoners. Women face widespread discrimination and violence.

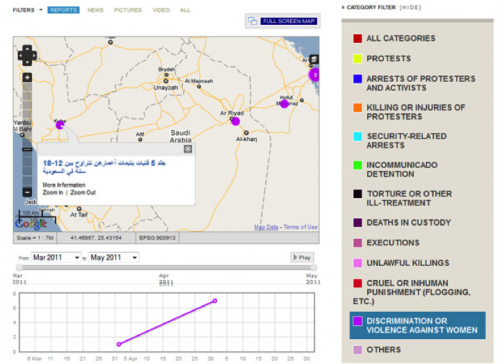

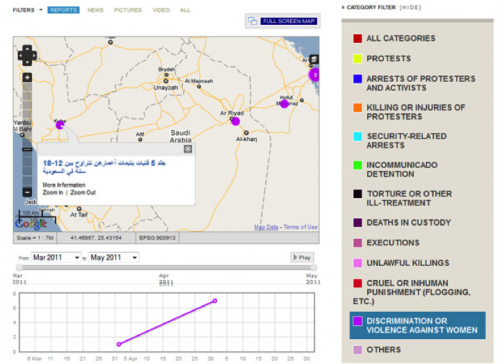

[caption id="attachment_4438" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Screenshot of Amnesty International’s Crowdmap of Saudi Arabia"]

[/caption]

While AI has played a leadership role in the use of new technologies for human rights monitoring—such as the use of geospatial technologies such as satellite imagery, crowd sourcing does not yet count as a standard methodology or data source in the work of human rights watchdogs. However, that might slowly change. Amnesty previously used crowd sourcing the context of activism and mobilization. For example, as part of the launch of its new flagship campaign to fight poverty, the organization created a platform to amplify the voices from Kenyans, who were describing their understanding of “Dignity”.

Saudi Arabia Crowdmap

The Arab Spring, with its massive popular uprisings and use of social media tools to organize, provides further urgency to test and expand the use of crowd sourcing, including gathering human rights related events information. Of all the countries in the Middle East and North Africa Amnesty chose Saudi Arabia to deploy its first crowdmap--a strategic—yet challenging—choice. The country has not received a lot of attention in the wake of the Arab Spring, and remains extremely closed and restricted, with little information outflow. We know, however, human rights violations are widespread and widely underreported. This is largely related to a prevailing culture of secrecy, no matter if in regards to the justice system or the specific conditions of (political) prisoners. Women face widespread discrimination and violence.

[caption id="attachment_4438" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Screenshot of Amnesty International’s Crowdmap of Saudi Arabia"] [/caption]

Freedom of expression is highly restricted, making Saudi Arabia in fact one of the most repressive governments in regards to freedom of expression online. While many social media sites are accessible and popular, specific content is subject to censorship, which is strictly enforced. For example, in August 2009 the government blocked the Twitter account of two human rights activists and authorities do not hesitate to detain critical bloggers.

However, Saudi online users used online tools successfully for crisis response in the past. During major floods in 2009, Saudis used YouTube to pressure authorities to investigate the inadequate response (check out Freedom House for a detailed overview of online freedom in Saudi Arabia).

Thus, Saudi Arabia was definitely an interesting test case. Another objective was to mainly target Arabic speaking communities, and in geographic areas in which Amnesty does not yet have a strong presence. The idea was to ideally receive reports from within country, using the usual channels (Twitter, SMS, email, online reports). While there was obviously interest to track any potential or emerging protests similar to other countries in the region, a look at the various categories on the crowdmap shows very clearly the strong focus on specific violations of human rights. The 12 categories included torture or other ill-treatment, deaths in custody or cruel or inhuman punishment (such as flogging), which are reflective of Amnesty’s long standing human rights concerns in the country.

Moderate Response

The project was initially planned for one month only (Mid April to Mid May). However, especially because of the recent developments and attention on the driving ban for women in Saudi Arabia, the test phase was extended for another month until mid of June. The response was moderate, with several hundred visitors to the site who contributed 54 reports in almost all categories over a two months period. The majority of the visitors came from the United States, followed by users from Saudi Arabia. However, what is interesting to note is that the majority of the reports were in Arabic, indicating that the limited but targeted outreach payed off. Additionally, the project gathered significant interest within Amnesty International, so that we are optimistic that we will see an increased use of crowd sourcing for advocacy and campaigning in the future, to complement Amnesty’s rigorous research methodologies. (Justified?) Skepticism definitely remains—you might notice that all reports on the Saudi Arabia crowdmap are clearly marked “unverified”.

Technology Is Bringing Us Closer – In All Aspects

Amnesty International is not simply a human rights NGO. It is a network of millions of people who have pledged in action and deed to the notion that all people must enjoy the rights established in the Universal Declaration. That is, Amnesty International is a crowd. And though technology has taken us far from the cafes, university classrooms, and community centers that had traditionally been the meeting place of those who would seek to defend the right of others they had never met, usually thousands of miles away—the technology is bringing us closer to the core of the Amnesty mission: to defend a global movement to ensure that all people—regardless of their circumstance or position—are empowered as agents to secure their rights, freedom, and dignity.

[/caption]

Freedom of expression is highly restricted, making Saudi Arabia in fact one of the most repressive governments in regards to freedom of expression online. While many social media sites are accessible and popular, specific content is subject to censorship, which is strictly enforced. For example, in August 2009 the government blocked the Twitter account of two human rights activists and authorities do not hesitate to detain critical bloggers.

However, Saudi online users used online tools successfully for crisis response in the past. During major floods in 2009, Saudis used YouTube to pressure authorities to investigate the inadequate response (check out Freedom House for a detailed overview of online freedom in Saudi Arabia).

Thus, Saudi Arabia was definitely an interesting test case. Another objective was to mainly target Arabic speaking communities, and in geographic areas in which Amnesty does not yet have a strong presence. The idea was to ideally receive reports from within country, using the usual channels (Twitter, SMS, email, online reports). While there was obviously interest to track any potential or emerging protests similar to other countries in the region, a look at the various categories on the crowdmap shows very clearly the strong focus on specific violations of human rights. The 12 categories included torture or other ill-treatment, deaths in custody or cruel or inhuman punishment (such as flogging), which are reflective of Amnesty’s long standing human rights concerns in the country.

Moderate Response

The project was initially planned for one month only (Mid April to Mid May). However, especially because of the recent developments and attention on the driving ban for women in Saudi Arabia, the test phase was extended for another month until mid of June. The response was moderate, with several hundred visitors to the site who contributed 54 reports in almost all categories over a two months period. The majority of the visitors came from the United States, followed by users from Saudi Arabia. However, what is interesting to note is that the majority of the reports were in Arabic, indicating that the limited but targeted outreach payed off. Additionally, the project gathered significant interest within Amnesty International, so that we are optimistic that we will see an increased use of crowd sourcing for advocacy and campaigning in the future, to complement Amnesty’s rigorous research methodologies. (Justified?) Skepticism definitely remains—you might notice that all reports on the Saudi Arabia crowdmap are clearly marked “unverified”.

Technology Is Bringing Us Closer – In All Aspects

Amnesty International is not simply a human rights NGO. It is a network of millions of people who have pledged in action and deed to the notion that all people must enjoy the rights established in the Universal Declaration. That is, Amnesty International is a crowd. And though technology has taken us far from the cafes, university classrooms, and community centers that had traditionally been the meeting place of those who would seek to defend the right of others they had never met, usually thousands of miles away—the technology is bringing us closer to the core of the Amnesty mission: to defend a global movement to ensure that all people—regardless of their circumstance or position—are empowered as agents to secure their rights, freedom, and dignity.

[/caption]

While AI has played a leadership role in the use of new technologies for human rights monitoring—such as the use of geospatial technologies such as satellite imagery, crowd sourcing does not yet count as a standard methodology or data source in the work of human rights watchdogs. However, that might slowly change. Amnesty previously used crowd sourcing the context of activism and mobilization. For example, as part of the launch of its new flagship campaign to fight poverty, the organization created a platform to amplify the voices from Kenyans, who were describing their understanding of “Dignity”.

Saudi Arabia Crowdmap

The Arab Spring, with its massive popular uprisings and use of social media tools to organize, provides further urgency to test and expand the use of crowd sourcing, including gathering human rights related events information. Of all the countries in the Middle East and North Africa Amnesty chose Saudi Arabia to deploy its first crowdmap--a strategic—yet challenging—choice. The country has not received a lot of attention in the wake of the Arab Spring, and remains extremely closed and restricted, with little information outflow. We know, however, human rights violations are widespread and widely underreported. This is largely related to a prevailing culture of secrecy, no matter if in regards to the justice system or the specific conditions of (political) prisoners. Women face widespread discrimination and violence.

[caption id="attachment_4438" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Screenshot of Amnesty International’s Crowdmap of Saudi Arabia"]

[/caption]

While AI has played a leadership role in the use of new technologies for human rights monitoring—such as the use of geospatial technologies such as satellite imagery, crowd sourcing does not yet count as a standard methodology or data source in the work of human rights watchdogs. However, that might slowly change. Amnesty previously used crowd sourcing the context of activism and mobilization. For example, as part of the launch of its new flagship campaign to fight poverty, the organization created a platform to amplify the voices from Kenyans, who were describing their understanding of “Dignity”.

Saudi Arabia Crowdmap

The Arab Spring, with its massive popular uprisings and use of social media tools to organize, provides further urgency to test and expand the use of crowd sourcing, including gathering human rights related events information. Of all the countries in the Middle East and North Africa Amnesty chose Saudi Arabia to deploy its first crowdmap--a strategic—yet challenging—choice. The country has not received a lot of attention in the wake of the Arab Spring, and remains extremely closed and restricted, with little information outflow. We know, however, human rights violations are widespread and widely underreported. This is largely related to a prevailing culture of secrecy, no matter if in regards to the justice system or the specific conditions of (political) prisoners. Women face widespread discrimination and violence.

[caption id="attachment_4438" align="alignnone" width="500" caption="Screenshot of Amnesty International’s Crowdmap of Saudi Arabia"] [/caption]

Freedom of expression is highly restricted, making Saudi Arabia in fact one of the most repressive governments in regards to freedom of expression online. While many social media sites are accessible and popular, specific content is subject to censorship, which is strictly enforced. For example, in August 2009 the government blocked the Twitter account of two human rights activists and authorities do not hesitate to detain critical bloggers.

However, Saudi online users used online tools successfully for crisis response in the past. During major floods in 2009, Saudis used YouTube to pressure authorities to investigate the inadequate response (check out Freedom House for a detailed overview of online freedom in Saudi Arabia).

Thus, Saudi Arabia was definitely an interesting test case. Another objective was to mainly target Arabic speaking communities, and in geographic areas in which Amnesty does not yet have a strong presence. The idea was to ideally receive reports from within country, using the usual channels (Twitter, SMS, email, online reports). While there was obviously interest to track any potential or emerging protests similar to other countries in the region, a look at the various categories on the crowdmap shows very clearly the strong focus on specific violations of human rights. The 12 categories included torture or other ill-treatment, deaths in custody or cruel or inhuman punishment (such as flogging), which are reflective of Amnesty’s long standing human rights concerns in the country.

Moderate Response

The project was initially planned for one month only (Mid April to Mid May). However, especially because of the recent developments and attention on the driving ban for women in Saudi Arabia, the test phase was extended for another month until mid of June. The response was moderate, with several hundred visitors to the site who contributed 54 reports in almost all categories over a two months period. The majority of the visitors came from the United States, followed by users from Saudi Arabia. However, what is interesting to note is that the majority of the reports were in Arabic, indicating that the limited but targeted outreach payed off. Additionally, the project gathered significant interest within Amnesty International, so that we are optimistic that we will see an increased use of crowd sourcing for advocacy and campaigning in the future, to complement Amnesty’s rigorous research methodologies. (Justified?) Skepticism definitely remains—you might notice that all reports on the Saudi Arabia crowdmap are clearly marked “unverified”.

Technology Is Bringing Us Closer – In All Aspects

Amnesty International is not simply a human rights NGO. It is a network of millions of people who have pledged in action and deed to the notion that all people must enjoy the rights established in the Universal Declaration. That is, Amnesty International is a crowd. And though technology has taken us far from the cafes, university classrooms, and community centers that had traditionally been the meeting place of those who would seek to defend the right of others they had never met, usually thousands of miles away—the technology is bringing us closer to the core of the Amnesty mission: to defend a global movement to ensure that all people—regardless of their circumstance or position—are empowered as agents to secure their rights, freedom, and dignity.

[/caption]

Freedom of expression is highly restricted, making Saudi Arabia in fact one of the most repressive governments in regards to freedom of expression online. While many social media sites are accessible and popular, specific content is subject to censorship, which is strictly enforced. For example, in August 2009 the government blocked the Twitter account of two human rights activists and authorities do not hesitate to detain critical bloggers.

However, Saudi online users used online tools successfully for crisis response in the past. During major floods in 2009, Saudis used YouTube to pressure authorities to investigate the inadequate response (check out Freedom House for a detailed overview of online freedom in Saudi Arabia).

Thus, Saudi Arabia was definitely an interesting test case. Another objective was to mainly target Arabic speaking communities, and in geographic areas in which Amnesty does not yet have a strong presence. The idea was to ideally receive reports from within country, using the usual channels (Twitter, SMS, email, online reports). While there was obviously interest to track any potential or emerging protests similar to other countries in the region, a look at the various categories on the crowdmap shows very clearly the strong focus on specific violations of human rights. The 12 categories included torture or other ill-treatment, deaths in custody or cruel or inhuman punishment (such as flogging), which are reflective of Amnesty’s long standing human rights concerns in the country.

Moderate Response

The project was initially planned for one month only (Mid April to Mid May). However, especially because of the recent developments and attention on the driving ban for women in Saudi Arabia, the test phase was extended for another month until mid of June. The response was moderate, with several hundred visitors to the site who contributed 54 reports in almost all categories over a two months period. The majority of the visitors came from the United States, followed by users from Saudi Arabia. However, what is interesting to note is that the majority of the reports were in Arabic, indicating that the limited but targeted outreach payed off. Additionally, the project gathered significant interest within Amnesty International, so that we are optimistic that we will see an increased use of crowd sourcing for advocacy and campaigning in the future, to complement Amnesty’s rigorous research methodologies. (Justified?) Skepticism definitely remains—you might notice that all reports on the Saudi Arabia crowdmap are clearly marked “unverified”.

Technology Is Bringing Us Closer – In All Aspects

Amnesty International is not simply a human rights NGO. It is a network of millions of people who have pledged in action and deed to the notion that all people must enjoy the rights established in the Universal Declaration. That is, Amnesty International is a crowd. And though technology has taken us far from the cafes, university classrooms, and community centers that had traditionally been the meeting place of those who would seek to defend the right of others they had never met, usually thousands of miles away—the technology is bringing us closer to the core of the Amnesty mission: to defend a global movement to ensure that all people—regardless of their circumstance or position—are empowered as agents to secure their rights, freedom, and dignity.