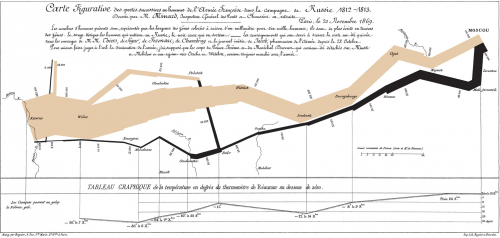

This image is the most important of my professional life. It depicts Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812, with the width of the line representing the size of his army and the two line colors marking the attack and retreat. It was created by Charles Joseph Minard using casualty data recorded during the campaign.

When I first entered my Ph.D. program, I had already long been an avid student of international politics and its history. I grew up reading history books and could describe everything from the main differences between pre- and post- Lenin communism to a, frankly, pretty impressive history of both World Wars off the top of my head. But what I didn't know was data.

On the first day of my Ph.D. program, they warned all us new students: "This is a quantitative program, we deal in statistics and data, that is our — and soon to be your — bread and butter." I blew it off. "I've used Excel before," I said to myself, "how much more complicated can this be?" I was wrong.

From day one, I struggled. Hard. Between statistical formulas, mathematical proofs, and calculus, I could barely keep my head above water. I made it through the first few months, but I hated it. "What does this all this math have to do with politics?" I thought. I even debated quitting.

Then, towards the end of my first year, I randomly stumbled upon this strange map of Napoleon's invasion. I had studied the invasion for years and I felt like I already had a good grasp of what happened. However, looking at Minard's visualization, I learned about an central aspect the campaign that I had never realized before: Napoleon didn't, as I had imagined, march into Russia only to have his full army routed at Moscow. Rather, he was suffering casualties from day one. By the time he reached the pivotal battle of the campaign, his army was only a sliver of its original size. This might not seem like a big deal to you, but to a student of political science, this insight rocked my world.

Nothing else in my professional life has affected me more than Minard's visualization. Why? Because it was an image that was only made possible using data. It, in the words of E.J. Marey “seems to defy the pen of historian by its brutal eloquence." That image made me realize that all those quantitative skills, from statistical programming or genetic matching models, weren't merely an end in themselves, but simply tools to help me to tell stories; stories that otherwise would be impossible to tell.

I tell this story because sometimes smart people — with years of experience in international development, journalism, or disaster relief — mention to me that working with data is only for "math people." But the truth is that at the end of the day, I consider what they do and what I do to be the same thing: trying to understand our world to make it a better place. So instead of leaving your data to the math geeks, enjoy it as a tool to tell stories that matter to you.

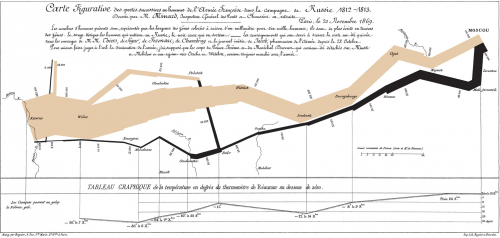

This image is the most important of my professional life. It depicts Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812, with the width of the line representing the size of his army and the two line colors marking the attack and retreat. It was created by Charles Joseph Minard using casualty data recorded during the campaign.

When I first entered my Ph.D. program, I had already long been an avid student of international politics and its history. I grew up reading history books and could describe everything from the main differences between pre- and post- Lenin communism to a, frankly, pretty impressive history of both World Wars off the top of my head. But what I didn't know was data.

On the first day of my Ph.D. program, they warned all us new students: "This is a quantitative program, we deal in statistics and data, that is our — and soon to be your — bread and butter." I blew it off. "I've used Excel before," I said to myself, "how much more complicated can this be?" I was wrong.

From day one, I struggled. Hard. Between statistical formulas, mathematical proofs, and calculus, I could barely keep my head above water. I made it through the first few months, but I hated it. "What does this all this math have to do with politics?" I thought. I even debated quitting.

Then, towards the end of my first year, I randomly stumbled upon this strange map of Napoleon's invasion. I had studied the invasion for years and I felt like I already had a good grasp of what happened. However, looking at Minard's visualization, I learned about an central aspect the campaign that I had never realized before: Napoleon didn't, as I had imagined, march into Russia only to have his full army routed at Moscow. Rather, he was suffering casualties from day one. By the time he reached the pivotal battle of the campaign, his army was only a sliver of its original size. This might not seem like a big deal to you, but to a student of political science, this insight rocked my world.

Nothing else in my professional life has affected me more than Minard's visualization. Why? Because it was an image that was only made possible using data. It, in the words of E.J. Marey “seems to defy the pen of historian by its brutal eloquence." That image made me realize that all those quantitative skills, from statistical programming or genetic matching models, weren't merely an end in themselves, but simply tools to help me to tell stories; stories that otherwise would be impossible to tell.

I tell this story because sometimes smart people — with years of experience in international development, journalism, or disaster relief — mention to me that working with data is only for "math people." But the truth is that at the end of the day, I consider what they do and what I do to be the same thing: trying to understand our world to make it a better place. So instead of leaving your data to the math geeks, enjoy it as a tool to tell stories that matter to you.

This image is the most important of my professional life. It depicts Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812, with the width of the line representing the size of his army and the two line colors marking the attack and retreat. It was created by Charles Joseph Minard using casualty data recorded during the campaign.

When I first entered my Ph.D. program, I had already long been an avid student of international politics and its history. I grew up reading history books and could describe everything from the main differences between pre- and post- Lenin communism to a, frankly, pretty impressive history of both World Wars off the top of my head. But what I didn't know was data.

On the first day of my Ph.D. program, they warned all us new students: "This is a quantitative program, we deal in statistics and data, that is our — and soon to be your — bread and butter." I blew it off. "I've used Excel before," I said to myself, "how much more complicated can this be?" I was wrong.

From day one, I struggled. Hard. Between statistical formulas, mathematical proofs, and calculus, I could barely keep my head above water. I made it through the first few months, but I hated it. "What does this all this math have to do with politics?" I thought. I even debated quitting.

Then, towards the end of my first year, I randomly stumbled upon this strange map of Napoleon's invasion. I had studied the invasion for years and I felt like I already had a good grasp of what happened. However, looking at Minard's visualization, I learned about an central aspect the campaign that I had never realized before: Napoleon didn't, as I had imagined, march into Russia only to have his full army routed at Moscow. Rather, he was suffering casualties from day one. By the time he reached the pivotal battle of the campaign, his army was only a sliver of its original size. This might not seem like a big deal to you, but to a student of political science, this insight rocked my world.

Nothing else in my professional life has affected me more than Minard's visualization. Why? Because it was an image that was only made possible using data. It, in the words of E.J. Marey “seems to defy the pen of historian by its brutal eloquence." That image made me realize that all those quantitative skills, from statistical programming or genetic matching models, weren't merely an end in themselves, but simply tools to help me to tell stories; stories that otherwise would be impossible to tell.

I tell this story because sometimes smart people — with years of experience in international development, journalism, or disaster relief — mention to me that working with data is only for "math people." But the truth is that at the end of the day, I consider what they do and what I do to be the same thing: trying to understand our world to make it a better place. So instead of leaving your data to the math geeks, enjoy it as a tool to tell stories that matter to you.

This image is the most important of my professional life. It depicts Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812, with the width of the line representing the size of his army and the two line colors marking the attack and retreat. It was created by Charles Joseph Minard using casualty data recorded during the campaign.

When I first entered my Ph.D. program, I had already long been an avid student of international politics and its history. I grew up reading history books and could describe everything from the main differences between pre- and post- Lenin communism to a, frankly, pretty impressive history of both World Wars off the top of my head. But what I didn't know was data.

On the first day of my Ph.D. program, they warned all us new students: "This is a quantitative program, we deal in statistics and data, that is our — and soon to be your — bread and butter." I blew it off. "I've used Excel before," I said to myself, "how much more complicated can this be?" I was wrong.

From day one, I struggled. Hard. Between statistical formulas, mathematical proofs, and calculus, I could barely keep my head above water. I made it through the first few months, but I hated it. "What does this all this math have to do with politics?" I thought. I even debated quitting.

Then, towards the end of my first year, I randomly stumbled upon this strange map of Napoleon's invasion. I had studied the invasion for years and I felt like I already had a good grasp of what happened. However, looking at Minard's visualization, I learned about an central aspect the campaign that I had never realized before: Napoleon didn't, as I had imagined, march into Russia only to have his full army routed at Moscow. Rather, he was suffering casualties from day one. By the time he reached the pivotal battle of the campaign, his army was only a sliver of its original size. This might not seem like a big deal to you, but to a student of political science, this insight rocked my world.

Nothing else in my professional life has affected me more than Minard's visualization. Why? Because it was an image that was only made possible using data. It, in the words of E.J. Marey “seems to defy the pen of historian by its brutal eloquence." That image made me realize that all those quantitative skills, from statistical programming or genetic matching models, weren't merely an end in themselves, but simply tools to help me to tell stories; stories that otherwise would be impossible to tell.

I tell this story because sometimes smart people — with years of experience in international development, journalism, or disaster relief — mention to me that working with data is only for "math people." But the truth is that at the end of the day, I consider what they do and what I do to be the same thing: trying to understand our world to make it a better place. So instead of leaving your data to the math geeks, enjoy it as a tool to tell stories that matter to you.